FSF Day – Making Cinematic Series

On Wednesday June 13, 2018, the very first FSF Day was held at the Swedish Film Institute in Stockholm. This was a special event arranged by The Swedish Society of Cinematographers (the FSF) with invaluable help from Jerry Axelsson from the Swedish Film Institute and great support from our sponsors Mediateknik AB and Panasonic.

It is the ambition of the FSF to make this a yearly reoccurring event, so we very much wanted this premiere edition to be a success. And although one might have been superstitious about choosing the 13th as the date for the event, everything worked out fine, the Victor Cinema (named after the great Swedish director Victor Sjöström) was filled up nicely and the proceedings went smoothly.

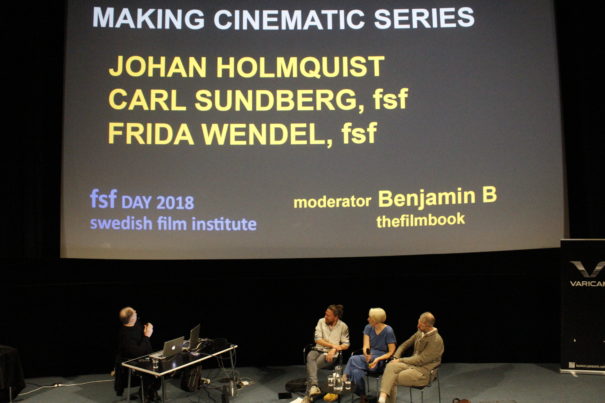

Moderator during the FSF Day was none other than the internationally acclaimed film journalist Benjamin B, author of the much appreciated book ”Reflections” in which he chronicles a number of cinematographers and their craft, and well known also for his blog ”thefilmbook”, which is published on asc.com, the ASC website.

Benjamin was involved with the design of the FSF Day, which is spearheaded by a Master Class featuring Irish cinematographer Seamus McGarvey, ASC, BSC.

At the FSF Day I had a chat with Jyri Hakala, FSC, who maintained that Making Cinematic Series was the part of the event which gave him the most satisfaction, simply because it lay closest to his everyday working conditions. And we are talking here of course about the first entry of the FSF Day: a long conversation between Benjamin B and three cinematographers currently working on TV series. They are Carl Sundberg, Frida Wendel and Johan Holmquist.

Benjamin came up with the title ”Making Cinematic Series” and he opens this lecture by asking the audience rhetorically ”I admit it’s a provocative word, but what do I mean by cinematic? Well not just ’better’, but basically not formulaic and not just coverage. By cinematic I mean storytelling that is visually interesting, original and which also has a certain style and mood.”

Benjamin believes that cinema is an art form, and that the serial format offers certain virtues which enable TV series to also be an art form. He feels that some of the best American cinema today is in TV series and that these series allow filmmakers to hide out from the superhero fare which dominates the big screens today.

The episodic format, he explains, was really introduced in the shape of serial literature in the 19th century, when -one chapter at a time- such works as The Count of Monte Christo, A Tale of Two Cities, Anna Karenina and Heart of Darkness -some of the greatest achievements in western literature- were originally published as serials in magazines and in little booklets.

Other bona fide masterpieces such as Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, which is now considered to be one of the most perfect novels of all time, and Crime and punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky, which is Benjamin’s idea of the most perfect novel of all time, were also created a chapter at a time in this manner.

So, this notion of releasing a narrative a short portion at a time has a great history and tradition.

According to Benjamin, The West Wing and The Wire were the pioneering works of this new cinematic art form and, he suggests, ”these two series together probably offer one of the best descriptions of American society from the top to the bottom. And being able to binge-watch a series was a transforming moment that made this new art form into multi-hour movies.”

”Features are about story, story, story”, Benjamin contends, ”but in a series, when you’re at episode eight you may not remember what episode two was about, so series become less about story and more about character, about entering a world, a universe.”

”Also”, Benjamin concludes turning to his panelists, ”series were invented in the USA, but you guys here in Scandinavia have proven yourselves very good at creating your own flavour of series, sometimes referred to as ’Scandinavian Noir.’ I’m thinking of titles such as The Bridge, Real Humans and The Killing -which in turn themselves have been copied abroad, completing the circle. You guys are also very good at creating quality material on lean budgets, and this leads us to what I wanted to talk to you about today, the challenge of managing time on a shoot, and how this will define your production method and your creative visual possibilities on a project.”

Transitioning smoothly over to the panel portion of the seminar, Benjamin explains he asked each participant ahead of time to write down a short list of their most important ”Commandments” to enable them to deliver high-class cinematography on a TV series.

This proves to be a very interesting approach to the subject, and first out is Carl Sundberg, FSF, who generously shares his experiences working on the TV series Bron (The Bridge). Carl has also shot installments in the Beck franchise of crime thrillers.

We watch a clip from Bron: the opening sequence of season two where a derelict ship threatens to ram the bridge.

The scene as it now is registers the action in a fairly straightforward fashion. Carl originally wanted to start this sequence staying on the boat letting the audience slowly discover that it is in fact an abandoned ship and then showing the audience that it’s going to collide with the bridge.

But besides the structuring of the material, Carl recalls there were many challenges in filming the sequence, ”first of all we ruled out shooting this at night, because we knew we could not light such a huge set, and secondly the entire thing — with the rented ship and helicopters and what have you — had to be shot in one day. Also, we could only find a fairly modest ship so it didn’t look all that threatening to the gigantic bridge.”

This is a good example of the kind of everyday situations on a shoot, involving the management of time and money, and it leads directly to Carl’s ”Commandments”, some of which are: ”avoid grand plans that fall short” (that one doesn’t require much extra explanation) and ”use wide compositions”, which triggers an interesting discussion.

In reply to Benjamin’s ”TV has traditionally been a close-up-medium, it started out that way”, Carl offers, ”Yes, and that’s why I like to make my compositions a little wider, so you give the audience a little extra orientation where we are geographically in each shot.” In other words, telling the story in slightly wider shots means you need fewer set-ups for a certain sequence.

”Choose locations you can control” is another piece of sound advice from Carl, who points out that ”there are cars parked in this street today -there will be different cars parked here tomorrow.”

He also stresses the necessity for thorough preparation, ”Fast, cheap and good”, he points out, ”you can normally only get two out of three of these, but with thorough preparation you can bend that rule a little, and one way of doing it is by highly detailed call-sheets: if everyone can see on the call sheet that scene 5 is supposed to take 30 minutes to shoot, then they all know what they’re in for when they arrive in the morning.”

Carl is also a firm believer in keeping to an eight-hour working day, and that’s door to door: from the truck leaving the garage in the morning to its return in the evening. And in order to be able to do that, Carl prefers that the actors rehearse prior to the shoot and not on the day of the actual takes. ”I’ve worked abroad”, he offers, ”and often on those shoots everyone sits around endlessly while the actors rehearse.”

”An eight-hour work day would be such a shock to an American crew”, Benjamin quips with a wry smile.

”Six-hour shooting days allows us to have a family on the side”, Carl maintains, ”Also it means there’s less dialogue to shoot every day, which takes some of the pressure off the actors. This means we effectively have six and a half hours on set each day, and one way to maximize the use of that time is for actors, director and cinematographer to meet a little earlier than everyone else on the set in the morning and just do the blocking. Then I have all the information I need to do my work during the day, and when the full crew arrives we can concentrate on getting the scenes.”

Next up is Frida Wendel, FSF, who is currently prepping a TV series for HBO and among other titles has on her CV the acclaimed Swedish science fiction series Äkta Människor (Real Humans).

She has just finished a series called Striking Out shot in Ireland for RTÉ, and several sequences from it are screened here to illustrate topics discussed. Lisa James Larsson, the director of Striking Out, is also in the audience here at the FSF Day so that invigorates the exchange of ideas considerably. The series follows a woman who works as an attorney in Dublin, and Frida emphasizes that ”the city of Dublin is really a central character in the drama.”

One of Frida’s ”Commandments” is to pick locations that have good natural light sources. She also likes a lot of movement in her work, to constantly keep the camera moving, and she uses a small Fuji digital camera to shoot short pre-viz sketches of the camera blocking to show to director and crew. She also enjoys working in the exact opposite way from Carl, rehearsing with the actors on the set and finding the setups on the spot. As shooting in Ireland allows for a maximum 12-hour working day, Frida and Lisa are less pressed for time than Carl was on Bron.

”It’s more of a feature film approach”, Benjamin notes, ”rehearsing on the day right before the actual takes.”

”Yes”, Frida concurs, ”but we also try to solve scenes in one continuous take which saves time, so it evens out. And we usually don’t have time to put down tracks for the dolly, so I try to come up with creative solutions for the camera moves.”

”Like combining an Easyrig, a dolly and a Maxima gimbal”, Benjamin points out.

When planning the days, frequently the filmmakers have additional set-ups they’d like to shoot, and often don’t have time to, and these have jokingly become known as ”the Flugan” (meaning the fly in Swedish, since the first of them was a ’fly-on-the-wall’ angle).

”So your motto became Get the Flugan”, Benjamin suggests, to the mirth of the audience.

Benjamin also offers as an example of a cinematic sequence a huge descending view of Dublin; this was accomplished with a drone and ”would have been a lot more expensive to do with a crane”, Benjamin points out.

”We wanted epic drone shots of Dublin in this series”, Frida explains, ”the city really is one of the key characters in the story.”

Lisa James Larsson points out that she feels drone shots in period piece films are a challenge to wrap one’s head around, ”it just feels wrong to have a drone shot in an era before there was any human flight at all.”

”Except if it’s the point of view of a seagull”, Benjamin jests.

A touching sequence from Striking Out depicts a child custody case. This one is particularly pertinent to today’s theme of time management, as the producers wanted several more shots at the end of the sequence, but Frida came up with an idea to cover the action in just two set-ups.

”She saved me there, as she often does” director Lisa James Larsson adds.

Johan Holmquist is our third panelist here today and he has among other things shot the TV series Arne Dahl (2015) and Springfloden (2016). The majority of clips screened during the seminar, to illustrate Johan’s ”Commandments”, are from Springfolden which was partially shot on location in France.

Johan asserts that his strategy ”is really about speeding up the regular work so that you have time to do the more cinematic shots, and one additional advantage of working with a French crew was that you always had one grip and two assistants on the set all the time”. So, using one of these extra grips, Holmquist could get extra tracks laid for additional scenes, even if there was sometimes no time to shoot them. So, in comparison to Frida’s experience where there was rarely time to lay tracks at all, Johan had the luxury of being able to order tracks laid for an additional scene which the crew sometimes had the time to shoot and sometimes didn’t. Needless to say, had those tracks not already been in place though, shooting this additional scene would have been impossible in any case.

Holmquist also feels that minimizing the amount of coverage you shoot is another good idea if you want to work quickly, and one way to do that is to shoot a scene from one direction only. This not only saves time, but the actors also frequently find it stimulating, they can give it everything they have on a couple of takes and be done with the scene, as compared with having to pace their performances so they’re able to do good work over dozens of setups of the same material.

Johan has an additional ”secret weapon” up his sleeve: ”if you see something good in another filmmaker’s work”, he suggests, ”just borrow it.”

”You mean steal it”, Benjamin offers with a wry smile. And he proceeds to run a clip from Springfloden involving a character who gets gunned down in the street. Johan confesses to a ”steal” here, the scene has been heavily inspired by a scene from Mike Nichols’ Regarding Henry (1991) where Harrison Ford’s character accidentally walks into a convenience store robbery and gets shot by a desperate robber chillingly portrayed by John Leguizamo.

And seeing this makes me realize John Leguizamo holds the distinction of killing off two of the greatest screen icons of the past 50 years of cinema: Harrison Ford in this one and Al Pacino in Carlito’s Way (1993).

So, in conclusion, to sum up ”Making Cinematic Series”, all three of these cinematographers Carl Sundberg, Frida Wendel and Johan Holmquist, are able to create memorable and cinematic work, even though they sometimes employ diametrically opposed methods, the common denominator at work here being to harness time, the management of time, and how it’s spent on the production.